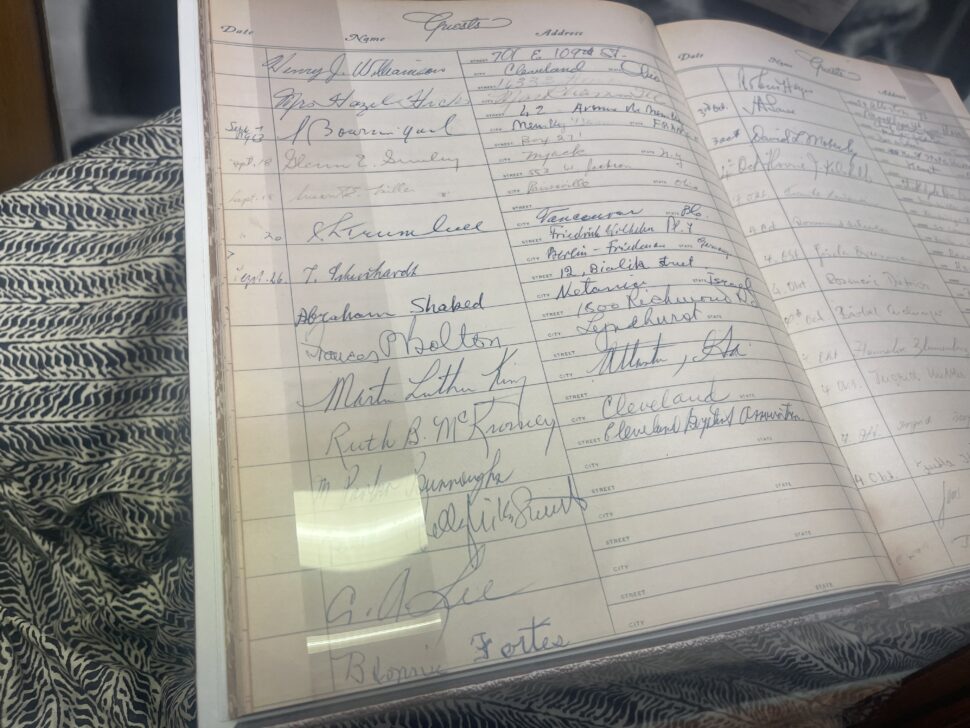

A signature in an open guestbook behind plexiglass in Karamu Houses’s hallways reads: “Martin Luther King. Hometown: Atlanta, Georgia.”

As you continue to walk down the hallways, there are other known autographs, signatures, and pictures of familiar faces that newer generations read about in history books.

A picture of Muhammad Ali with the first African-American mayor of a major city, Carl Stokes, sits behind another display. Stokes was elected mayor of Cleveland in 1967. He’s also the first Black Democrat elected to the Ohio House of Representatives.

Keep walking, and there are photos of Sidney Poitier, comedian Flip Wilson, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, and James Pickens Jr., best known as Dr. Richard Webber in Grey’s Anatomy. Pictured next to these is a photo of Russell Jelliffe and community members at Karamu before heading to the 1963 March on Washington.

“There were more buses that left the Karamu House for the March on Washington than any place in Ohio,” Tony Sias, Karamu House president and CEO, tells Travel Noire.

Minnie Gentry, the great-grandmother of actor Terrence Howard, is on the wall. Upstairs is the “Langston Suite” – a room paying homage to where one of the greatest Black writers of all time, Langston Hughes, would work.

Guests won’t find these pictures anywhere else in the world. They serve as a testament to how this gem, on the intersection of Quincy Avenue and E 89th Street, became the longest Black-producing theater in the country.

Two Black Boys Changed Karamu’s History

Karamu didn’t start as a theater. Russell Jelliffe and his wife, Rowena Woodham Jelliffe, originally created a settlement house named the “Playhouse Settlement.”

“Settlement houses, in short, were early forms of social service agencies. When founded in 1915, we primarily served Eastern European immigrants,” says Sias.

The Jelliffe’s created a common ground where people of different races, religions, and social and economic backgrounds could come together to seek and share common ventures. The arts were the common ground at Playhouse Settlement, and plays began shortly after in 1917.

As Black families migrated to the North during The Great Migration, many moved into Jewish communities in Cleveland. Two little Black boys saw people acting from outside the settlement porch one day. They asked Mrs. Jelliffe if they could come in, and she welcomed them inside. This gesture was the beginning of the integration of Karamu House.

“This speaks to the consciousness and the progressive thoughts of our founders,” says Sias. “They were serving their people, but when others moved to the community, they chose to serve others. They understood that we are much better together than separate.”

In 1941, there was a naming competition for the theater. Hazel Mountain Walker, an actress and the first Black female principal in the Cleveland public school district suggested Karamu.

“Karamu is a Swahili word that means ‘a place of joyful gathering in the center of the community,'” says Sias. “We’ve abbreviated that today to mean a place of joyful gathering.”

Moving Forward With History At The Forefront

Karamu – a preserver of Black culture and African American history, is still putting on outstanding productions that ensure stories are told through the Black lens and perspective.

“There are not many places that do this in the country,” says Sias. “Karamu represents less than 3 percent of theaters in this country where the Black experience is the center of its mission.”

It’s currently undergoing four phases of renovations and a refresh to better serve people in the community.

“This renovation has really focused on creating an environment in the heart of the historic Fairfax Community for 21st-century patrons and theatergoers. It’s also about accessibility,” Sias says.

Sias wants the theater to be accessible in an unpretentious and inviting way. Some updates include a new restaurant and a larger bar and lounge area to serve the nearly 200 guests the main theater can hold.

Another exciting touch is the indoor and outdoor space that connects the north and south sides of the building. It features a garage-style door where Karumu will hold concerts, receptions, and other entertainment events such as jazz concerts, comedy shows, and an orchestra.

Karamu’s southside portion of the building – along Quincy Avenue – has a revamped streetscape near Cleveland’s thoroughfare known as “Opportunity Corridor,” connecting the city’s east and west sides.

“We’re activating the south side of the building as our ‘porch to the community,'” Sias adds.

To ensure its legacy continues through the next generation, there’s a new studio space for content creation. Sias says teaching young people new skills is vital to Karamu’s mission.

“This is aligned with workforce development. That’s important because in Northeast Ohio, for example, there are 93 theaters, including professional, nonprofessional, community, and educational. There’s a wealth of opportunity to work.”

He adds, “We want to be able to train people through our technical theater workforce development. These theater skills are transferable over into film and television. We know that films and film productions are coming to Cleveland.”